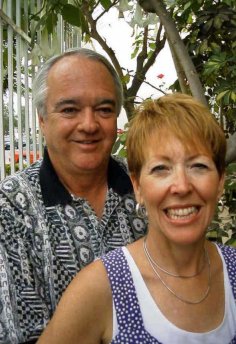

Walter Leaman – December 2005

Walter Leaman lost his courageous battle with pancreatic cancer on October 27, 2006.

Vital Statistics

Walter Leaman was diagnosed in August 2002, at the age of 59, with Stage IV inoperable adenocarcinoma . His prognosis was approximately 6-8 weeks to live. Treatment was clinical trial chemotherapies: Gemzar/Cisplatin; later Gemzar/Oxaliplatin. Care was received at the University of California at San Francisco, which has an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. His oncologist was department head Dr. Margaret Tempero. Walter’s primary caregiver, his wife Jean Leaman, also contributed to this story.

Background

Walter and Jean live in Danville, California, about 30 miles east of San Francisco, where they own and operate a family business. They have three grown children, one of whom – along with her husband and a grandchild – lived with them during the period of this diagnosis and treatment.

Medical Journey – Pancreatic Cancer Diagnosis

In the spring of 2002, stomach problems first sent Walter to their long-time general practitioner. The next four months were spent pursuing the prevailing theory of a developing ulcer. At that point, a second consult with GP Dr. Lowell Kleinman led to an endoscopy and biopsy. When those were negative, he ultimately recommending exploratory surgery to ascertain the precise problem.

The surgeon was a highly rated one, although not a pancreatic cancer specialist. The morning after the surgery, he arrived in Walter’s hospital room, in near-dawn-darkness, to announce: “We were hoping we would find lymphoma, but we didn’t. I’m so sorry to tell you that you have Stage IV pancreatic cancer. It has spread to your stomach and your liver, there is some lymph node involvement, and I’m so sorry there’s nothing we can do for you.” Then, with tears in his eyes, he left Walter – quite literally – in the dark.

The laparoscopic surgery had indicated a large mass protruding from the body of the pancreas and adhering to the posterior wall of the stomach. Lesions, also biopsied as malignant, were present in the liver as well. In a separate conversation with Jean, the surgeon predicted that her husband probably had about six to eight weeks to live.

Walter’s mind was a blur. “How could I go from having a little stomach pain to dying, this fast?” Jean had a somewhat different reaction. During the long waiting period, she had been on the web doing endless research, and had actually come to the conclusion – from the symptoms and the location of the pain – that it just might involve the pancreas. When she mentioned that possibility to the gastroenterologist doing the earlier endoscopy, he was dismissive. “But when the diagnosis finally came through,” says Jean, “I wasn’t surprised.”

Both describe the next couple of weeks as a surreal transition stage – “a grieving process”. But as with many couples, they differed in their overall reactions to the news. Asked for a word to describe his feeling then, Walter says “resignation”. Jean says “fighting-back”. Walter started writing down instructions for cleaning the pool filter. Jean started shopping for hope.

Next stop was the San Ramon Regional Medical Center, where they met with head oncologist Dr. Peter Wong. The Leamans’ goal by then was modest – to get a firmer prognosis on the number of weeks left. To their surprise, Dr. Wong had a different goal. “I want to have Walter back playing golf within a year.” It was the first positive thing either had heard since this dire diagnosis, and tears – and possibilities – began to flow.

Dr. Wong was aware of some clinical trials being conducted by a colleague, Dr. Margaret Tempero, head of oncology at the University of California San Francisco (and member of Pancreatica.org’s Science Board). “If anyone can help you, she can,” said Dr. Wong. Fortuitously, a particularly promising trial was about to start. It involved two drugs now common in cancer treatment: Gemzar and Cisplatin.

Medical Journey – Pancreas Cancer Treatment

And as the life-giving chemo began, Walter started feeling some hope for the first time. But most friends and family, knowing little about this disease and all of it bad, were (despite best intentions) not exactly surrounding them with encouragement. By the time the trial began, Walter was in serious back and stomach pain and had lost a total of 50 pounds. “It was no surprise to anyone who saw me that I was very near death.” They know many of their friends were feeling they were in denial. Even three years out, “some probably still do”.

By the end of the first three weeks, nausea, smell-sensitivity and balance problems had entered the picture. But Walter’s pain and other symptoms were subsiding, eating was getting easier, and the positive vibes were increasing.

Recovery

Walter did not experience some of the Whipple-specific dietary problems, since he did not qualify for that procedure. However the disease, combined with the effects of the chemo, did make him disinterested in eating at some points. “It’s not the chemo that kills you, or the cancer, but that you starve yourself to death.” During those periods, Jean had to force eating, and sometimes resort to tough love: “You can eat here, or you can go back to the hospital and get an IV. And trust me, they won’t be as nice about it as I am…”

Visualization played a helpful role at times. During chemo, Walter would sometimes imagine his chemo infusions as a group of ducks, cleaning up the cancer cells by going around the edge of ponds, as he’d often seen them do. At other times, he experienced some relief when he focused all his healing energy, once as his grandson, then later his cat, instinctively rubbed/kneaded his stomach. “I’ll never know for sure what worked, but I’m giving them all the credit they deserve just for trying!”

In communicating about Walter’s situation with their young grandchildren – especially the one that lived with them – they kept it simple.

Grandpa’s sick, and we’re all trying to help him get better.

“

Cancer Free!” In January 2004, 16 months after the terminal diagnosis, Walter and Jean heard the words they never expected to hear. That was the good news. The bad news was that, as often happens, the relentless impact of the Cisplatin had seriously affected his kidneys. The prospect of dialysis loomed, and Walter had a dilemma. He was in uncharted territory – the chemo regimen was keeping him alive, but what would happen when it stopped? Doctors advised him that, at this point, the kidneys were more likely to kill him than the original problem. So, chemotherapy ceased and bimonthly CT scans continued.

15 months passed. Then in the spring of 2005 a tumor reappeared, this time on Walter’s adrenal gland. Dr. Tempero resumed treatment, this time pairing Gemzar with Oxaliplatin, another now-common cancer drug then in trials. Incredibly, the tumor again responded. By the fall of 2005, it was gone again – with no further recurrence so far.

So Walter remains in watch-and-see mode, with CT scans continuing every 60 days. “By now, I glow in the dark,” he says. But two side effects are with him as well. First, a new but not-uncommon one, peripheral neuropathy – an ongoing numbness in the fingers and toes. Second, the damage to the kidneys makes it dangerous to use the standard “IV Contrast” which helps to provide clear readings on the all-important CT scans. So while they think things look good, it’s difficult to be sure… A nephrologist is now stabilizing the Creatinin levels, and is recommending the use of a “kidney coating” medication (Mucomyst) that may permit the full (contrast-enabled) CT scans to resume.

“This illustrates one of the unique problems with people who beat the odds, probably with any disease,” Jean observes. “The medical community doesn’t quite know what to do with you next. The clinical trial saved you. But it caused other problems. And since you’re the rare exception, there are no known solutions yet, in many cases, to those new problems.”

Walter’s Most Important Resources

Online sites most used included: WebMD.com; UCSF.edu; Pancreatica.org; PanCan.org; and the searchable listserv archives at CancerCare.org.

The listserv convened by the Association of Cancer Online Resources (ACOR) – a national volunteer-led non-profit organization linking cancer patients and their families and caregivers with information, support and community. Their pancreatic cancer listserv group is one of the most active and supportive online. Says Walter, an active user: “I wish I’d found that earlier.” Interested readers may join here:

http://www.acor.org/pancreas-onc.html

Activity-wise, Walter did get fully back to his golf game, and spends a great deal of time organizing tournaments for himself and about 40 other business owners and friends in the Bay Area. His other interests seem to revolve around like-minded others. He volunteers. He talks with people across the country who are in his situation. He also makes himself available for seminars and conferences, either on panels or in what-works workshops with other survivors.

Spirituality? In a formal sense, Jean is more connected to the specific belief in a higher being, but both of them clearly are attuned to many things affecting the spirit and soul. “Walter has quite an extensive network of friends, colleagues and fellow PC families, always encouraging them to keep up the good work. I think things like that are his version of spirituality.” He adds, “lots of people know me and my situation. When I send out status Emails to the group, I make a point to be jovial, but factual, and say ‘to those who thought we were done, tough luck!’ And many people have been praying for us. That’s ok, too.”

Obviously the experimental drug protocols are what the medical team would point to as responsible for Walter’s success. But to the Leamans (and they think Dr. Tempero and her colleagues would probably agree), it’s because “we kept on not giving up, kept on thinking positive. Which is not to say there weren’t times….”

The role of hope and the power of positive thinking first entered the picture at the initial meeting with Dr. Wong and his golf course goal. It increased with Dr. Tempero’s news about the treatment that just might work. Says Jean, “If we hadn’t heard those things, Walter would have been gone in a very short time. If you don’t find that person that instills hope, keep looking. It absolutely can change your outcome.”

Pancreatic Cancer Advice

For caregivers:

- Do your research. “Especially when you’re going through the pre-diagnosis stage, you should not just wait on the doctors – they’re handling loads of people and you are in charge of just one. They’re still ‘the doctors,’ but it’s crucial for you to try to know almost as much as they do, so you can contribute to the solution.”

- Keep taking it to the next level. Says Jean: “That’s what I had to do with every single doctor we went to. If I didn’t get the right appointment, I went to the next doctor that would give me that appointment till I got what we needed. I don’t know why, but I always felt that if we could get the right treatment for Walter, he just might have a chance.”

- Force eating. “And don’t overly obsess about the quality of the food. I wasted time in the beginning cooking the recommended things, bringing them in, and having them rejected because of the smell or other things. So I began just asking “what DO you feel like: Chicken soup? Thai? Ice cream? Whatever – you can have that morning noon and night, I don’t care. Unlike normal times, it’s the calories that count.”

- The importance of an advocate. Remember the two very different reactions Walter and Jean had at the time of diagnosis? When asked if it would have been any different had Jean not been there, Walter says, “I wouldn’t be here at all if it weren’t for her. She is absolutely the greatest. If anything still does happen, I know she’ll be well taken care of…dozens of my friends are ready and waiting to marry her and take over where I leave off!”

Advice for patients

and caregivers alike comes in the form of this cautionary tale. In this current stage of CT scanning problems, Walter’s medical files have been prominently marked “DO NOT USE CONTRAST – POTENTIAL KIDNEY FAILURE.” Once, very recently, after the IV was inserted and he was lying horizontal about to enter the tunnel, Walter said “just making sure – you’re not using contrast in that IV, are you?” They were. And

everyone was thankful that he spoke up. Medical professionals are still human. Don’t assume – protect your

own self.

Friends have been a godsend to this couple. Especially so are those who, knowing that it’s not over till it’s over, keep the offers coming even after months, even years, have passed.

Advice to friends

Ask “what’s on your

list today?” While friends and neighbors want to help, they often aren’t sure how. A common way is to say

Call me if you need anything. Seemingly similar, but importantly different, was one friend’s way of putting it:

What’s on your list today…what can I do to help with something? “Many times, what was on my list was something non-medical and seemingly unimportant (like getting the oil changed in the car, or picking up the dry cleaning). I would have never thought to bother others with those. But in fact, at the time, those things might be weighing heavily, as we were burdened with other priorities.” An offer stated that way can also reassure the family that indeed “today is a particularly good day for me to help you.”

Well-meaning things not to say? Jean’s nomination is “How is he,

really?” “Also, don’t assume that chemo means that we can’t have any fun. We aren’t always ‘sick’. We still like to go out to dinner sometimes too!”

Laughter is often the best medicine. Says Jean, “that’s what I had to have, for me. Walter had his meds, but I had nothing to take! I had to have an outlet, every day, to take me away from the reality. TV, a joke, special friends – laughter.”

Two stories demonstrate the power of laughter for the Leamans:

When they first learned the details of this illness and the likely financial implications, they realized that some serious scaling-back was in order. Jean took matters into her own hands and began the process, by actually having a yard sale to clear out lots of items they wouldn’t have room for in the event they needed to downsize to a condominium. By the following spring, however, things were looking up, and when it came time for Walt to prepare the little plot for his annual tomato garden, he couldn’t seem to find his hoe. “Have you seen my hoe anywhere?” he asked Jean – who sheepishly replied, “Oops…sorry about that!”

Shortly before diagnosis, Walter had finally been persuaded to shell out a lot of money for hearing aids. In the early post-diagnosis period, there were of course some dark and scary days. “That’s when Jean would tell me that I’m not going anywhere until we get our money’s worth out of those darned hearing aids.”

As told to Alison Wiley, an oral historian working with people and organizations to recall and record their important stories.